Product Metagaming: Theme Parks vs. Sandboxes

Contextualizing product experiences big and small and the rules that govern them.

Admittedly, I am unsure how to begin this post amid *motions hands* everything. This was an observation first made a year ago, but something always came up when it came to writing it down. Whenever it was time to write about it, as soon as I open up the outline- something more critical arose, and off I would go doing other tasks.

Game design and trends are on my mind lately. Witnessing the first modern cross border internet rule-set develop between rising and incumbent powers took me back to simpler times. Times when I could procrastinate on required readings to delve into video game patch notes. Not to abstract human impact, but it feels like tech juggernauts' meta policy on their products subject people to games where they don't exactly know the rules to.

This last week, we had the privilege to witness Jeff Bezos speak on mute. More importantly, see how four major US tech giants fare under U.S. congressional oversight. I won't be talking about geopolitics or anti-trust in this post, but stay with me, there's a common thread.

I argue social media platforms and marketplaces have a metagame similar to most multiplayer video games. Wikipedia defines metagame as "approaches to games operating beyond the game's prescribed rules." Many video game consumers interpret a meta to mean the trend of how people approach a game versus others. The game rules might favor one weapon that is easier to use over others.

Touching on the companies represented at the anti-trust hearing. You can consider the laws and PR efforts they undertake as part of a metagame. Sure, congressional hearings are part of a company's responsibility. However, these CEOs would much instead be focusing on making decisions that would lead to a positive revenue impact. Being in tech where legislators don't have a complete understanding of that business means that scrutiny is done somewhat extrajudicially. These are the winds of change that they don't really have direct control over. And these unwritten norms and markets in which these companies operate shift. It's why Facebook adopted a different stance on political speech than Twitter. Players of these games don't have direct control over how the game is designed or changed. Still, most, if not all, players are subject—even the people who design the games themselves. Most of these business observers reference their positioning as strategy.

Now, unlike the congressional republicans, I don't think that there is an explicit algorithmic bias towards conservative views. But there is an algorithmic bias that favors certain types of content over others. On major products, Dungeon Masters of our social networks that define the rules, and the players on those sites conform to the meta. Its why every post on LinkedIn

Looks

Like

This.

Patch Notes and Twitter Meta

I used to play DotA. It's the precursor to League of Legends where a fmr. Game-designer went on to co-found Riot Games. One of my favorite past times was to dig through the patches and completely obsess on those changes that would affect the play style. To give the community time to adjust, they would announce these changes well in advance. There would often be an enterprising community member on forums replying giving hot takes on which characters will become preferred to play. Teams of all skills would adapt quickly and change their tactics to fit the conditions once patches were deployed should they choose to play that version of the game. Very similarly on Twitter, I feel product fans and entrepreneurs behave very similarly to the DotA community. Both communities are interested in the second and third order effects of primary changes of behavior from fellow players in the space.

Many observers in the social communication app space noticed a new meta in consumer-focused start-ups that focused on synchronous communication. Many developers started thinking about how we spend our time online for reasons that might be linked to the pandemic. Product fans and those who fund those products shared their thoughts on where and where we spend our time. A new dichotomy started floating around Twitter- sync vs. async. I think the classification is apt, Ryan Dawidjan reframed the discussion as "My Time" vs. "Our Time" applications. Even more apt.

However, I believe that product teams of all products not only should think about how their products are consuming their customer's time- shared or privately. We should be having a more considerable discussion if the product experience they are building gives the end-user the requisite amount of trust to feel fulfilled. If there's one thing to glean from the hearing, those who interact with marketplaces and end-user products want to know the rules. Bipartisan confusion on whether their campaign emails will go to spam means there is a significant misunderstanding from users of all stripes about product expectations. If recent discourse on algorithms on the internet as given any hint to product developers is that there is growing curiosity around what constitutes a person’s recommendation diet.

In addition, it's not enough for product teams to create a tool to release in the wild and hope it gets adoption. For many in the entertainment and social spaces, the discussion around making your content your moat misses the point. You need your products to empower creatives while also delivering to those to wish to be entertained. I think there is a better dichotomy to think about understanding the product experiences you want to offer. More on this soon, but first, another segue.

Massively “Differentiated” Multiplayer Games

There was a pivotal moment when modern server technology transcended beyond the age of the toaster. The cost of bandwidth lowered. Many technologists were the first to rightly point to the number of software start-ups that grew and gained dominance since then. One trend was going on in gaming in parallel. As multiplayer game engines got better server netcode to handle more clients. The rise of the Massively Multiplayer Online game arose. First, they were in the form of Multi-User Dungeons; text only realms that contained multiple people but were relatively limited in visual experience.

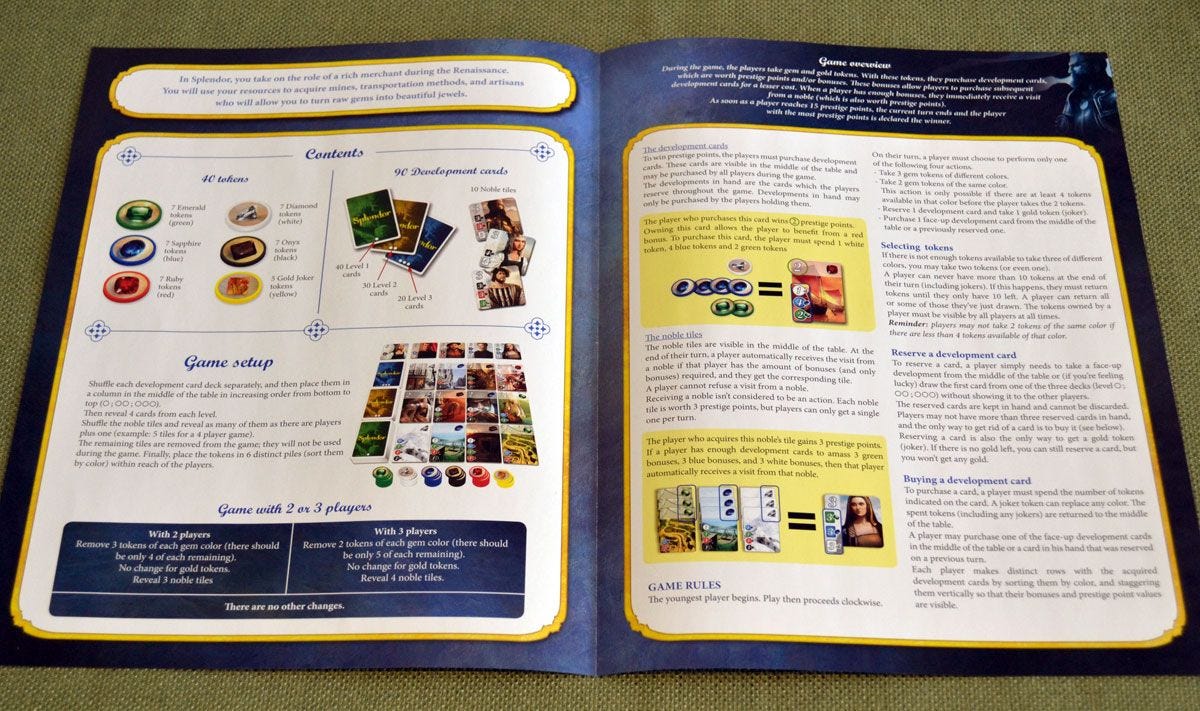

The format would evolve truly with a game released in 2000 called Everquest. It was the first commercially successful 3D Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game. You had servers with 100s of people on them, and you can do quests *together*. Keep in mind that not all subscribers could play with each other all at the same time. In that year, only 2 MMOs were released. I want to point out how much of a fad these games were. From the years 2001-2010, you had 116 unique MMOs come out. Compared to only 50 from 2011 to 2020. It was where these game companies got their first taste of subscription revenue.

For those uninformed, players would pay around ten to twenty USD a month to get a character in a fantasy realm. Within these realms, click within the virtual world to defeat some Non-Player Characters to gain XP to level their characters. Game designers would offer quests that would involve them clearing out the camps of Non-Player Characters that another player just handled 5 minutes ago.

During this boom period, much was done to innovate on this pattern, but the games systematically were very similar. There was a period where teams were trying to get the right balance of rules. Some experimented on delivery methods, Jagex's Runescape took advantage of Java web applets to deliver it's MMO to users in 2001. There were a few games that got loyal player bases and grew quite well, but there was one that needs no introduction whenever anyone mentions MMO.

World of Warcraft

For those unfamiliar, Blizzard, the game developer, for lack of better comparison is the Disney of game development studios. Like Disney, they have a rich set of IP in a suite of properties that allow them to harvest and revive their franchises at will for near risk-free revenue. World of Warcraft was built off their Warcraft franchise of Strategy games. Familiar characters, with weak penalties for character death, and proper pacing in character progression were able to foster a vast player base due to brand loyalty and subtle innovation in the genre. (For reference, Star Wars Galaxies another popular MMO at one point required players to play for around a year to become a Jedi) The level design of their worlds had more of a theme park feel compared to their rivals which had very bland worlds in comparison. Players not only delighted in building their characters but traveling within the game to enjoy the sights.

Like theme parks, players only were allowed to do what the game designers allowed them to do. There was strict moderation that player harassment was kept at manageable levels. If any mistake occurred with a player's items, GMs could always step in and resolve the matter. As players reached the highest levels, they could participate in synchronous activities such as raids. Guilds formed to be the unit of organization for those groups. Behaving similarly to families who would try to nab FastPass slots at Magic Kingdom(tm) appropriately respond to the timed nature of those events.

Almost every other game in this genre would try to copy the casualized nature of WoW and follow the formula to make games that were easy to play. Except one…

One year before, a game studio from Iceland named CCP released EVE Online. They partially funded the development from board game sales. EVE Online is a space-themed MMO. It's hard to describe this game, so I will tell you what it isn't. It not a theme park. The interface resembles more excel than it does a video game. It had one of the highest learning curves out of any MMO out there. It set itself apart by containing all players in the same game world instead of separating them into separate servers, meaning that all players can interact with all online players simultaneously. Due to this, new game dynamics occur. You have a player-driven economy with a robust commodities trading view. Player entities such as alliances can conquer space and declare war on other player entitles. You have literal space geopolitics. Player progression at one point was at risk of being lost if you didn't insure your character. While the developers used to have an economist on staff to care for the in-game economy to make sure inflation was kept in check. The game developers would market this game as a sandbox.

As the above screenshot suggests: CCP would prioritize facilitating player choice over attraction based gameplay like many of their competitors. As a result, the libertarian nature meant that the game would stay around the 300,000 subscriber mark during the MMO hype cycle peak. It was not and possibly still not a welcoming game, but it led to vibrant player-to-player interaction.

EVE's subscriber count pales to the comparison of WoW's subscriber count (12 Million at its peak). Most other games don't have the longevity as these two games have had. I exclude Second Life because Linden Lab requests that it is not classified as one.

Keep in mind that the problem space for many MMOs is similar. As publishers wish to accomplish business objectives, developers want to make sure users stay engaged but don't want to give the reward too early or too late. Player to player moderation is vital as well. Fraud is a significant concern. What's interesting to note is that the developers solved similar problems in entirely different ways. In WoW, you spent your time doing what is expected of you on the rails of what Blizzard offers you. For a while, if a player wanted better cosmetic items, you can buy them with gold earned in-game, trading, or through drops. If you wanted to spend money to acquire said items, the only option was to go on the grey market and buy in-game currency from a "gold farmer." Said gold farmers were against the ToS and left you at risk for a ban. Market sentiment was firmly against paid cosmetics at the time, and an item shop wasn't added until later.

CCP Online approached in-game currency liquidity by just introducing a FIAT money on-ramp to its in-game currency. You can purchase "in-game time" cards to renew your subscription and allowed you to sell unclaimed game time for in-game currency on the in-game market—much more of a laissez-faire approach.

Over time, as MMOs matured, game designers increasingly evaluated player choice and consequence to create a more interactive and meaningful experience. Despite this, most MMOs suffered intense boom and bust cycles within leading to their shut down in around 5 years. Whats notable about these examples is that they are the few games with staying power that stayed relevant in the market with two extremes of game design. As these games grew, passionate communities rallied around these games. They built communities that expanded beyond the boundaries of what these would games offer. What kept players coming back to each was whether the world was imprintable or if the world was an escape.

A Theme Park vs. A Sandbox

We’re All Game Designers Now

Those aforementioned Tech CEOs are all game designers. You can view the offerings of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Google straddling the line between theme park and sandbox. These platforms have their own moderation, game rules, and bounds of creativity that is deemed acceptable on their services. Some of their products land on the theme park side of operations. Hypothetically, user input is limited to consuming content or perhaps offering feedback in the form of a review. Some of their products are in the sandbox territory, whereas as users behave within bounds, they are allowed in the sandbox to create and show off what they have made.

Today’s product experiences can be segmented on the amount of rails that are put in place to get users to perform intended behavior. Some products want users to click on ads. Some of the very same products want users to contribute to the platform to give users a reason to click on ads. Depending on the monetization models, user creativity can be both celebrated and punished depending on the context. On Amazon’s Marketplace, sellers are highly discouraged from deviating from a certain quality bar on the marketplace. Punishment can come in the form by Amazon themselves or user reviews. A more sandbox-like version of Amazon could be Etsy, where seller creativity is expected from the company and the end-user.

Despite Jack Dorsey absence from the hearing. This framework highlights the true gulf between Twitter and Facebook lies in the amount of serendipity that can occur on each platforms. I feel like the closed social graph of Facebook reminds me that I am in different realms of the same universe rather than one connected world. Whenever I jump between those two products, I get the same disjoint feeling switching from my World of Warcraft character vs. my EVE Online pilot.

When you reduce the amount of rails on your product, you are simultaneously increasing the burden on the user to express themselves. On Facebook, the content is suggested and upcycled. On Twitter, you have both time, interaction velocity plus you are competiting with 300 Million other active streams of consciousness on the same shard. As a result, the sandbox with the more difficult learning curve has such a strong and dedicated user base. I argue that sandboxes and their requisite tools build a separate kind of loyalty- muscle memory. Where theme parks rely on the brand of their attractions that they offer within the product. This is reflected in Facebook's answer to product development to make more destinations and attractions within the site (Dating, Marketplace, Gaming) rather than enriching the open peer to peer communication component of the site itself. Twitter has a barely operable DM system with compelling people whom I wish to speak to wish. It’s a remarkably sticky product for a small subset of users. It's arguably, very much, a sandbox compared to the Facebook Theme Park.

Product teams can use this mental model to determine how to best seed content within their products and decide whether they need to build more attractions or focus on the core mechanisms like enabling user creativity. This dynamic is an and, not an or. Product teams should be dedicated to designing their systems to be a careful balance between rigid control (if need be) and open communication. This determination can help new teams decide if the feed needs to be sticky or if the social graph needs prioritization.

Some Closing Thoughts

The main difference between MMO sandboxes and theme parks compared to tech products is that games are remarkably explicit about the rules that govern these realms. In both of the MMO examples I have described, players are the customers- not the product to advertisers. As a result, how users consume the meta differ drastically. Much has been said about fairness in tech, but in our efforts to starve spammers, we have left users in the dark. That set of DotA patch notes that I would pour through was posted out due to a rabid player base expecting clear communication from the developers or they would leave to a different fork of the mod. Players would invest time learning and acquiring items and skills in these games. If these hard-earned skills were to become suddenly devalued, there would be a revolt. It's baffling to see companies, where arguably more capital is supported on these platforms, change the meta and rules for users that disrupt their physical livelihoods.

For stewards of these sandboxes and theme parks, much like the video games that many of us enjoy, companies should be more upfront about how systems behave. The issue with the ranking systems and marketplaces we have is hostile actors still subtly take advantage of building their content in ways that hijack these rulesets to get favorable outcomes for them. Many of us remember Elsa-gate, where spam generated children's videos took advantage of shock humor to rope children into watching inappropriate content. YouTube tends to take a silent approach with its creator management, seemingly demonetizing creators at will.

There are "rules" in place, but they are arbitrarily enforced. By approaching their products similar to MMOs, there can be greater understanding on why products behave the way they do. I hope that as users, we demand more from what we use. If not achieved, today's product developers can differentiate by offering greater trust for those that participate in the sandboxes and theme parks of tomorrow.

Hey Angelo here! If you liked this post consider sharing and subscribing. I do appreciate serendipitous discussions around ramblings of all kinds, my DMs are open on Twitter over at @ndneighbor

It’s a rough world out there, let’s remind ourselves to be kind and charitable to one another.